We’ll meet you all at the editorial office…

We all love Dungeons & Dragons. Whether it’s playing, exploring the lore, or finding resources like items and stat blocks, we all have our own passions. Many of us want to share that passion with others. If you have hopes of working in the industry, that might mean putting a price tag on that passion.

One of the most popular creative activities is publishing adventures or one-shot modules. If you’ve been a DM before, you might think you know how to write the material people want. And you might be right. But like a great boss fight, being a great DM is only the first step in the fight.

As with any adventure, the essential parts of a module are a good hook, a good path, and a clear idea of how to run the module. However, writing notes for personal use and knowing how to write a professional adventure module for DnD are two very different things.

There’s a lot to consider beyond the adventure itself, mainly because you’re not writing for yourself this time: you need to know what other DMs want and need.

So, if you’re looking to get started on creating a DnD adventure module, read on.

(Sneaky) Plot and Structure

If you’ve DMed before, this might seem like the easiest part: you know how to write the story, create sweet segments for your characters, and introduce cool callbacks that will get everyone excited.

But herein lies the first problem: you don’t know the tables, you don’t know the characters, you can’t tell the end user how to play the game. Sure, you can write 50,000 words per action trying to cover all the ways the player might interact with your writing, but you can’t use backup ideas to guide the action.

You need to trust the DM who is buying your adventure, and to do that, you need to make their life easy.

Don’t overload the story

Something to consider when writing stories for other people is to keep things simple. In the last campaign I ran for my own players, the players encountered a time-traveling illithid monster, which triggered a time loop, leaving the players to fight against themselves from an alternate future in-universe.

They had a great time, and the story made sense (for the most part) in context, but turning it into something other people could run was not possible for me — there are too many moving parts. It was a great adventure, but it doesn’t make for a great adventure module.

If I wanted to capture some of those elements and turn them into something others could use, I’d cut it down quite a bit, such as making an illithid monster the main enemy. There’s still a lot you can do with it, and including a few notes that it’s time travel would allow the eventual DM to come up with their own ways of tying it into a longer campaign. But keeping it simple makes it more approachable.

Not too long, not too short

Not only complexity matters, but length does too. When writing a professional adventure, it’s best to aim for a one-shot, at least at the beginning, because many people who buy adventures are looking for something they can run for a special occasion, or to get a friend into a game.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t a demand for longer adventures — once you’re comfortable writing for others, go wild with modules — but for those just starting out, keeping it short and sweet is best.

For one-shots, there’s a simple formula that works for just about everyone (though it may not work for more advanced adventures): Here’s how to write a DnD adventure module that maintains a comfortable pace.

A short introduction Easy to medium combat sequences Most of the adventure is focused on roleplaying Boss fights A short conclusion

It may seem like a pretty formulaic rule, but it’s actually quite liberating: too much combat can become boring, especially at lower levels, and too little can frustrate people who want to try out different classes and races.

Of course, I’m not saying you shouldn’t break away from this formula — one-shots that focus on a long battle with a single boss might be fun, or a more traditional dungeon crawl formula might be fun — but if you’re looking to pace a module over a single session, the formula above generally works well for around 4-5 hours of gameplay.

Notes and citations

Writing for others isn’t just about writing about the adventure itself. It’s also about how you write it. And this is perhaps the biggest challenge.

When writing notes for yourself, you might be a DM who likes to pre-plan a speech or paragraph of description to read to the players. Or maybe you make a note of “goblins” and “kingdom” and then improvise an entire conversation with the local greenskins when the time comes. But you’re not writing notes for yourself anymore.

DMs are all different, and you never know which type will buy your adventure. Hopefully, it’ll be both, so don’t plan on targeting just one or the other. There will always be some who don’t like your style.

When I write adventures for others, I tend to write bullet-point notes about what the scene is about, what activities the players might pursue, and a final paragraph suggesting when they should take the next step. I like to leave the control firmly in the hands of the DM and leave the explanations up to them, but I include enough detail so that the DM doesn’t find it difficult.

But my way is not the only way: some DMs don’t like coming up with detailed descriptions themselves, and some prefer the freedom to create details while still taking advantage of my broader ideas and resources.

It’s hard to know what the right answer is, but it’s something to consider when writing: be too prescriptive and you risk taking control away from both the DM and the players, but leave too much to the imagination and your customers won’t get their money’s worth.

Give them something to take home

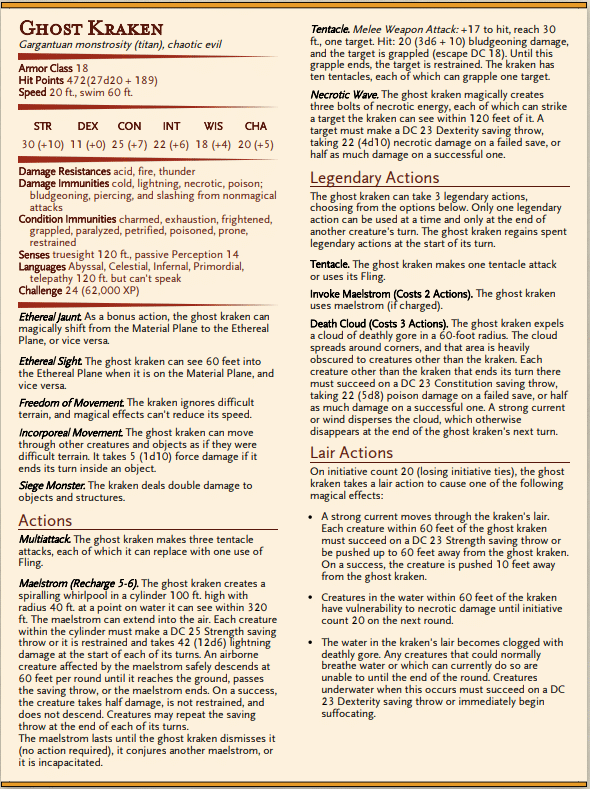

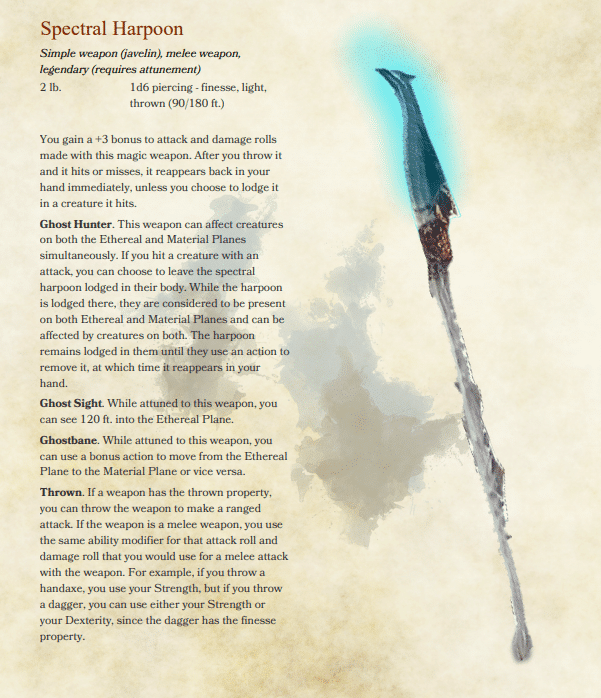

The following Ghost Kraken stats and Spectral Harpoon are taken from the latest Golem Factory adventure, “Into the Stormtide,” available now.

The great thing about DnD is that both the player and the DM have something to gain. I’m not talking about satisfaction, although that’s great too, I’m talking about loot.

Players love new items, and they add something special, even if it’s just a standalone one-shot, but an item that strikes a chord with both players and DMs isn’t exclusive to that adventure — it might carry over to another campaign or become a legacy item that stays on the table into the future.

The inclusion of unique items (and even unique monsters, if you’re a DM) is what makes the adventure more valuable rather than just being a one-off.

Final Tip

Items aren’t the only thing a DM can take away. Every DM has something to add to the game, whether it’s mechanics, puzzle creation, or a great story. If you can incorporate that into the adventure, you’ll give these DMs even more to incorporate into their future games. And that’s the true proof that you’ve accomplished something with your writing.

Robin Langfield Newnham is the founder and owner of Golem Factory, where he writes adventures and creates content for 5th edition Dungeons & Dragons. Golem Factory’s latest adventure for 20th level characters, “Into the Stormtide,” is available here.

Fill out the form below to receive your free copy of “Escape From Mt. Balefor”!

Or follow us on Instagram, Twitter and YouTube.